WHEN Sakura no Mori hospital and care home in Kawaguchi, 20km north of Tokyo, hired its first foreign workers six years ago, some of the patients would shout “gaijin” (“foreigner”) to summon them; others were wary of having anything to do with them at all. Today Verlian Oktravina, a 26-year-old Indonesian nurse, says the Japanese she works with are more curious than hostile. Yoko Yamashita, the director of the care home, says patients can see that foreign workers are as good as Japanese ones: “They accept them.” She herself, she admits, was initially sceptical about hiring immigrants, but has since changed her mind.

Acceptance of foreign labour is gradually increasing in Japan, one of the world’s most homogenous countries, where only 2% of residents are foreigners, compared with 16% in France and 4% in South Korea. A poll conducted last year found opinion evenly split about whether Japan should admit more foreign workers, with 42% agreeing and 42% disagreeing. Some 60% of 18-29-year-olds, however, were in favour, double the share of over-70s.

Whatever Japanese think of them, foreign workers have become a fact of life, at least in cities. There are 1.3m of them, some 2% of the workforce—a record. Although visas that allow foreigners to settle in Japan are in theory available only to highly skilled workers for the most part, in practice less-skilled foreigners are admitted as students or trainees. The number of these has been rising fast. Almost a third of foreign workers are Chinese; Vietnamese and Nepalese are quickly growing in number.

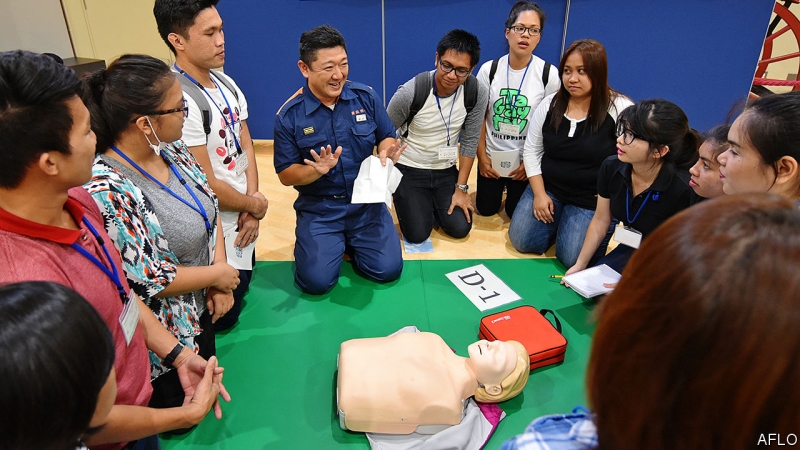

More gaijin are on their way. In June the government announced that it would create a “designated skills” visa in order to accept 500,000 new workers by 2025, in agriculture, construction, hotels, nursing and shipbuilding. More significant than the number, perhaps, is the government’s willingness to admit lower-skilled workers openly, rather than through the back door. “It is not the Berlin Wall coming down, but it is a significant shift,” says David Chiavacci of the University of Zurich.